Gerardo Criales: "History had already been written, but they never told us."

Gerardo survived one of the biggest natural disasters of the 20th century. One, he told OffMap Media, that could have been prevented.

In 1985 the Nevado del Ruíz volcano in Colombia erupted, wiping the town of Armero, where Gerardo lived with his family, off the map. Today its ruins — a modern Pompeii — stand as a place of remembrance for the thousands lost and a testament to how government failed them.

In his own words:

My name is Gerardo Criales. I was born in Armero, Colombia, in 1965 and today, I am the director of the Armero Historic Center, a project founded two decades ago to preserve the memory of those who died on that tragic night in 1985.

Armero wasn’t buried, it was erased. Around 30,000 people perished,1 my mother among them. I was 19 years old.

We interviewed Gerardo in January, as part of an article for Rouleur Magazine where we told the stories of the mountain and those who built their life on its slopes.

First off, you need to understand that Armero wasn't some small town as one might imagine. It was a prosperous, cosmopolitan city with five banks, two movie theaters, and a regional hospital.

That November 13, 1985, in the early hours of the afternoon ash began to fall. It’s a pretty normal phenomenon for volcanoes. But for us, it wasn’t normal.

On the news, they told us that this sort of thing happened with volcanoes and that the important thing was to avoid breathing in the ash – they told us to put on face masks and glasses, to make sure the ash didn’t get into our eyes. That’s it.

Then, at around 9:30 PM, there was an eruption. A big one.

Nobody heard it. We didn’t realize because that night it had started to rain. That was one of the factors – one of the things that contributed to “the perfect storm.” The other was the priest, who held mass and told everyone not to leave their houses unless they had to.

As I said, it was raining hard. I’d been out visiting my girlfriend and walking home from her house, I listened to the radio.

That’s another thing – supposedly that night there’d been warnings [on the radio]. Well, I fell asleep listening to a football match and at no moment was there any sort of interruption, any sort of transmission.

I came back to this world to my father shouting for me to wake up. “Gerardo, the river! it's coming for us!”

I reached for the light switch. Nothing. The first thing the avalanche destroyed was the power station. There was no light.

I grabbed keys and headed for the door. That’s when I felt the floor begin to tremble. It felt like being on an airport runway right as a huge passenger plane, like a 747, takes off. A shocking, deafening noise.

The black mud had already come down and started to fill the calles. It had formed hills blocking the main streets but, [thankfully], we lived on a carrera.2

Then, I suddenly remembered, “my grandfather!”

My grandfather slept in a room in the back of the house, so I had to go to the back patio and practically knock down the door. This lost us precious minutes.

The avalanche suddenly surrounded us and it carried us up. The mud stream took us to a height of about 7 meters.

My mom had been with my dad. One moment she was holding his hand. And the next moment, she was gone. My father turned to me and said, ‘your mom, I don’t know what happened to her.’ We think that maybe she thought we’d lost our grandfather – who was her father – and went back to help him. We just don’t know.

At this point, we had nowhere to run, so we stayed put. The night was long, filled with moans, people calling for help, but it was dark and we were unable to move.

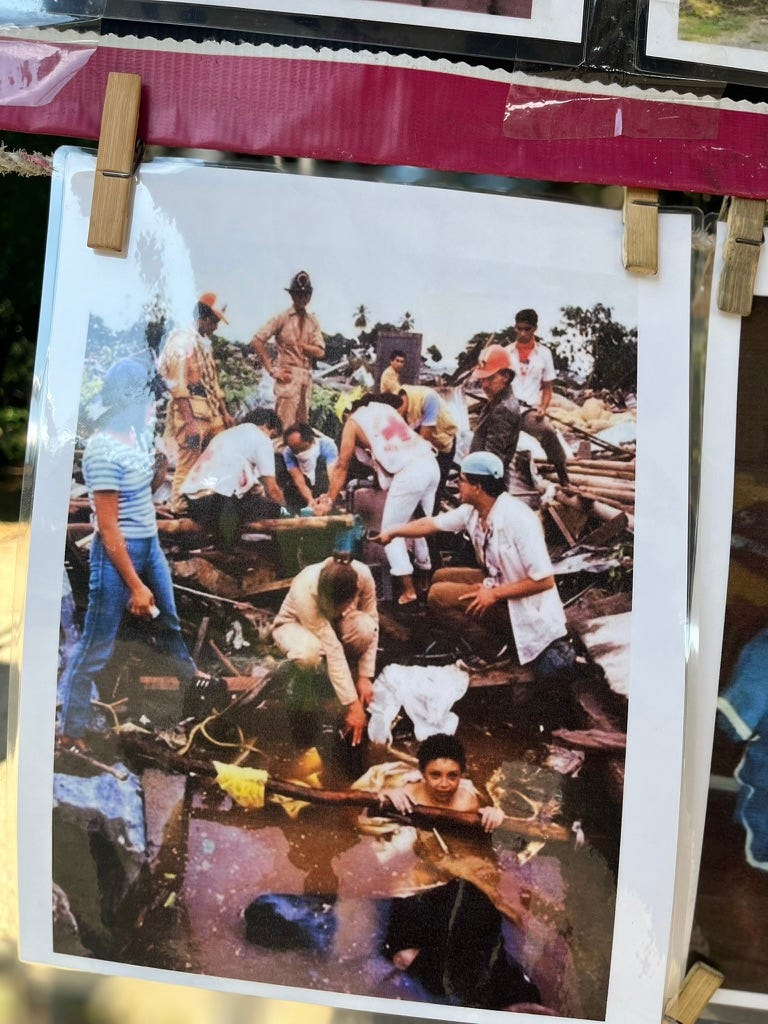

The next day, we began the process of helping get the wounded out and getting out ourselves. To our tremendous surprise, we found my mother just meters away, trapped under the power cables that had come crashing down in the avalanche.

She’d gotten tangled in the electricity cables when the poles fell. They threw her backwards and – I believe – she died from a blow to the skull. I looked for a tool, anything, to get her out. I cut the cables, I freed her. Then, I saw my grandfather who had also been trapped up to his waist by the same cables. But he was still alive!

“Mijo, I can’t feel my legs,” he moaned.

I freed him and started pinching and massaging his legs to get the circulation going.

The whole time, thinking: “He’s going to be disabled. This happened at 11 at night. It’s now 8 in the morning. He’s spent practically 12 hours without blood circulating in his lower body!”

But I’d gotten him out and he was alive. To do that, however, I had to leave my mother, as if she weren’t a human being, as if she didn’t have a family.

That Thursday, we did the impossible. We got out.

First, a small helicopter, which only really fit two people, picked my grandfather, my dad, and me up. I had my feet hanging out. To get us picked up, I had to make a kind of helipad so the pilot could try to get as low as possible and we could jump on.

I threw down planks and roof tiles. While collecting these materials, I saw a woman with her belly exposed, she’d been cut open. I covered her with a plank of wood and laid down other planks – it was the only way for us to get over her and out of the rubble. Later, speaking to my family about our missing aunt Raquel, I realized that it was her – that we’d stepped on top of my Aunt Raquel to escape, to get my grandfather to a hospital in Bogotá.

My dad and I weren’t hurt, but we left with just the shirt on our backs.

The helicopter dropped us off on a hill and we made our way to [the town of] Honda. From there, a kind stranger picked us up.

“Armero survivors?” he said. “I’ll take you to Bogotá. Don’t worry about food, I’ll take care of you.”

The whole ride, it was raining non-stop. At some point, his truck got stuck, and we had to get out and push. Imagine being in just a t-shirt, shorts in the brutal cold and rain, we got soaked. But, not for nothing, we made it despite the rain.

After a month [in Bogotá], my dad went back to help friends look for their belongings in the rubble. When he returned from the trip, I asked him what he’d seen.

“They took your mother’s body,” he said, adding that all of our belongings – the area where we’d left her – had turned into a sinkhole.

Three months later, in February, I went myself.

I was about to start my studies in Bogotá and I felt that I had to go back. I told a cousin and he said, “Why? Why would we go there to bring back bad memories? But if you want to see what’s left, it is up to you.”

And I went, and I found my mother’s body.

She was still there! I was in shock. My father had told me she had been collected, but here she was. [Later I learned] that my dad had confused the location of our house.

I told an aunt. “My mom, your sister, is still there. I left her the day of the disaster, and she is still there, waiting for me to come to give her a Christian funeral.”

The following week I came back with two uncles – her brothers. I went to a classmate, a friend who now worked in the police station, and asked her to help me get a death certificate.

“No, Gerardo,” she told me. “That’s difficult. That’s become a business.”

Remember that we had five banks. [After the tragedy], many people tried to get death certificates [for Armero victims] so they could get at their savings – take over their bank accounts. They would claim that whatever body was their mother, their aunt, whatever.

So I went to the notary’s office, to the registrar’s office, to the mayor’s office, but nobody would help me.

In the end, my dad got a permiso ligero to bury her, but I wasn’t going to bring my mom’s remains to Bogotá.

So, my mom remained there, where she was loved, where she was the mistress and lady of her house. We buried her on the patio and put up a commemorative plaque. She’s been there for 39, going on 40, years now.

The State was negligent, negligent with the municipality of Armero. The State knew what could happen in Armero, they knew it. They had already been talking to volcanologists – from Italy, North America and, I think, Japan.

That night, the mayor got the warning about the eruption at 9:30 — just after it happened.

He tried calling the governor. He called and called, but the governor was at the club — at a party. The story goes that the governor finally told him to stop being so alarmist, that nothing was going to happen. The mayor told the governor that an avalanche was heading down the Lagunilla riverbed, which – you know – posed a serious risk. The governor never paid him any attention.

That man died by the phone at City Hall, waiting for the governor to get on the line and give the order to evacuate.

Can you imagine what would have happened if the governor had ordered an evacuation at 9:30 when he got the first call? It took two hours for the avalanche to descend. We could have had two hours [to evacuate].

Moreover, Armero had already been destroyed by avalanches twice before 1985 – once in 1565 and again in 1845. The history had already been written but they never told us. In school, we learned about colonization, about the fight against the Spanish … they should have taught us about this.

The fact that a month before [the eruption], they made a risk map, but they never distributed it… the state knew what could happen, but the people were left completely in the dark.

And that is why we preserve the history here, at the Center. Because those who don’t know their history are bound to repeat it.

Recommended listening: Authorities made many mistakes in finding children’s parents or giving children a new home after the disaster. Radio Ambulante made an excellent episode about that (in Spanish).

Estimates of total deaths vary. Most sources give a number in the low 20,000s.

In Colombia streets that run north-south are called calles and ones that run east-west are called carreras.

We passed by on our way to Murillo. The size of this disaster is hard to comprehend until you're on the ground with the deserted streets and half-buried houses. This is another great story that brings these parts of the continent to life with words and images. Keep it up, OffMap!