SPECIAL REPORT: ‘Carnival of Despair’ as Ecuador’s Elections End in Tie

Amidst security concerns, constitutional crises, and growing public doubts, the country held its first round of presidential elections… and failed to choose a president.

*This story is published in collaboration with Pirate Wire Services. It was last updated on February 10.

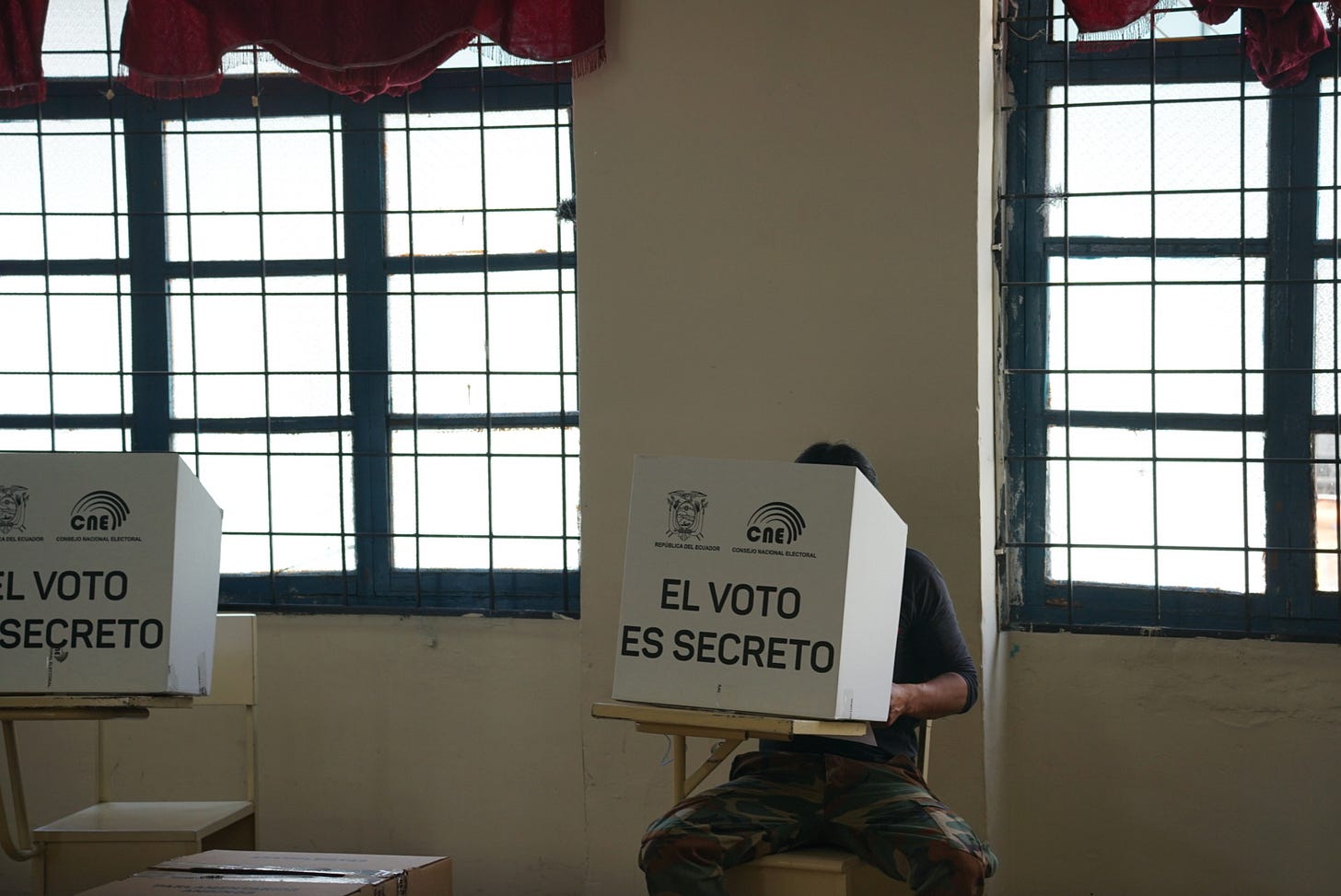

The streets of Quito had a carnival feel, as crowds of Ecuadorians pushed past street barbecues and artisans, making their way to the polls to vote for their next president and assembly members on Sunday.

Outside voting stations men and women barked offers to laminate voting cards for $0.25. Voting is obligatory and Ecuadorians will need to present their voting card as proof when opening a bank account, signing a lease, or trying to emigrate abroad.

Others strolled around with heavy loads hawking homemade snacks, juices, water, and soda – alcohol being prohibited on election day. Enterprising families set up stalls selling snacks like bolón, a local treat of fried green plantain stuffed with cheese.

“You make money. But it's more about spending time with family and sharing your food with others. It's a tradition,” Christian Arbolera, a bolón vendor told OffMap Media. “We always always set up a stall at election time.”

But, after a harrowing year marked by security, economic, and constitutional crises, these festivities masked an undercurrent of anxiety and exhaustion among a populous who said they saw little real leadership to choose from.

Unexpectedly Close

In fact, Sunday’s election ended in a virtual tie as a divided electorate failed to choose which of two controversial candidates they liked less. Ecuadorians will have to return to the polls on April 13.

With more than 93% of ballots counted at noon on February 10, the vote is split between sitting President Daniel Noboa, and his main rival, Luisa González - both of whom received about 44% of the vote.

Polls predicted a runoff but they did not predict such a tight race.

16 candidates ran in the first round of Ecuador’s presidential elections. To win a candidate needed at least 40% of the vote and at least a 10% lead against the runner-up. A record 83.3% of Ecuador’s eligible voters participated in elections this year, according to Ecuador’s National Electoral Council (Consejo Nacional Electoral - CNE).

Noboa, who exit polls predicted would win a large majority of the votes, ran for the National Democratic Action (Acción Democratica Nacional - ADN) party, which he founded in 2023.

González led the ticket for Citizens’ Revolution (Revolución Ciudadana - RC), a party mired in controversy. Its long-time leader, former president Rafael Correa, is exiled in Belgium and has an arrest warrant against him in Ecuador on bribery charges.

In April, González and Noboa will face off for the second time in 16 months. They were also the two final candidates in the November 2023 special elections, called after then-president Guillermo Lasso dissolved the government.

Leonidas Iza, leader of the country’s main indigenous party, took home 5,3% of the vote, followed by the leader of the liberal environmental Patriotic Society party (Partido Sociedad Patriótica), Andrea González, who won 2,7%. The other 12 candidates are far behind – all with less than 1% of the vote. The results of April’s vote will now depend on which candidate – Noboa or González – can rally more support among these two candidates’ base.

“We’d Love a Third Option”

When asked if she was excited to vote Jaqueline Sánchez rolled her eyes and laughed. “We’d love a third option,” she said. “But it's the same thing again. And again. And Again.”

Election fatigue was a common theme among those exiting the polls, with some telling OffMap Media they would not be there if the law didn’t mandate it.

“No, I’m not excited to vote. We’ve gone to the polls more than five times in four years,” an economist working in the energy sector, who asked to remain anonymous for fear it could hurt his ability to work with the government, said. “There are 16 candidates, but 90% of their proposals are the same and they have little credibility as such,” he added.

Ecuadorians last elected their president, Daniel Noboa, just over a year ago. That election dominated news cycles, especially after gang members killed one of the candidates, Fernando Villavicencio, on the campaign trail.

Noboa, then a rookie in the legislature who barely registered in presidential polling, reacted to the murder with hardline rhetoric promising to bring down the state’s “mano dura” (iron fist) if he won. That resonated with a terrified electorate, which got Noboa enough votes to pass into the second round. There, he capitalized on the momentum by positioning himself as an “outsider” running against establishment candidate, Luisa González.

González carries heavy political baggage in the form of her political mentor and the RC’s once-leader, Rafael Correa, president from 2007 to 2017.

Along the coast and outside of the cities Correa is still revered for pouring money into social spending and overseeing a drastic fall in poverty.

“A genius like Correa only comes around once every hundred years,” said Marco Billais, who voted Noboa in the previous elections, but now longs back to the days of Correa.

But for much of the rest of the country, Correa’s name is synonymous with authoritarianism and corruption. For many, the sitting president is less of a candidate in his own right than the only alternative to Correismo’s return — and perhaps the return of Correa himself.

“Noboa. We voted for Noboa,” Maricia Luna said before we could even ask a question. “We’re voting against socialism and we see no third option on the ticket — no one with potential.”

“I vote for Noboa because I don’t want to migrate,” her niece, Christina added. “I love my country. I want to have kids and raise them here in Ecuador. But if the left comes back into power I’ll have to migrate.”

“We Need Transparency”

Noboa had the most visible campaign, at least in Quito. The president – in aviators, dressed for the office, for a day at the gym, or in casual jeans and a T-shirt – looked out at voters seemingly from every storefront and apartment window. His cutouts in the city were ubiquitous.

But among those who displayed them and spoke to OffMap Media, their enthusiasm was lackluster. Many expressed desperation for consistency and told us they're supporting Noboa despite, rather than because of his record over the past year.

One older couple, whose cafe was guarded by a Noboa cutout, said they hoped, given more time, its living counterpart could do more for the country. They named security as their main concern, and though Noboa boasts he has made the country safer, the couple had no glowing reviews.

“No! Nothing is ok here,” said the older man, who asked not to be named. “There should be police here at all hours. Instead, there are thieves. Nothing has gotten better.”

Noboa declared an internal state of conflict in January 2024, kicking off a year marked by militarization – of the streets, the prisons, and political rhetoric.

At first, these hardline policies seemed to yield results with homicide rates falling.

But cases of extortion and kidnapping continued to rise unabated and the modest security gains eventually gave out as criminal groups adjusted to the new reality. The national murder rate remained well above pre-pandemic levels and January 2025 was Ecuador’s most violent on record.

“The situation is fatal. You walk around terrified that someone is going to assault you. I got robbed at gunpoint recently.” said Fernando Ron, a 79-year-old retiree and widower and Noboa supporter. He explained that since his wife died he likes being out of the house to keep busy, but worries he’ll be robbed again. “My daughter lives in Sweden and as soon as my papers are ready I’m going to emigrate too,” he said.

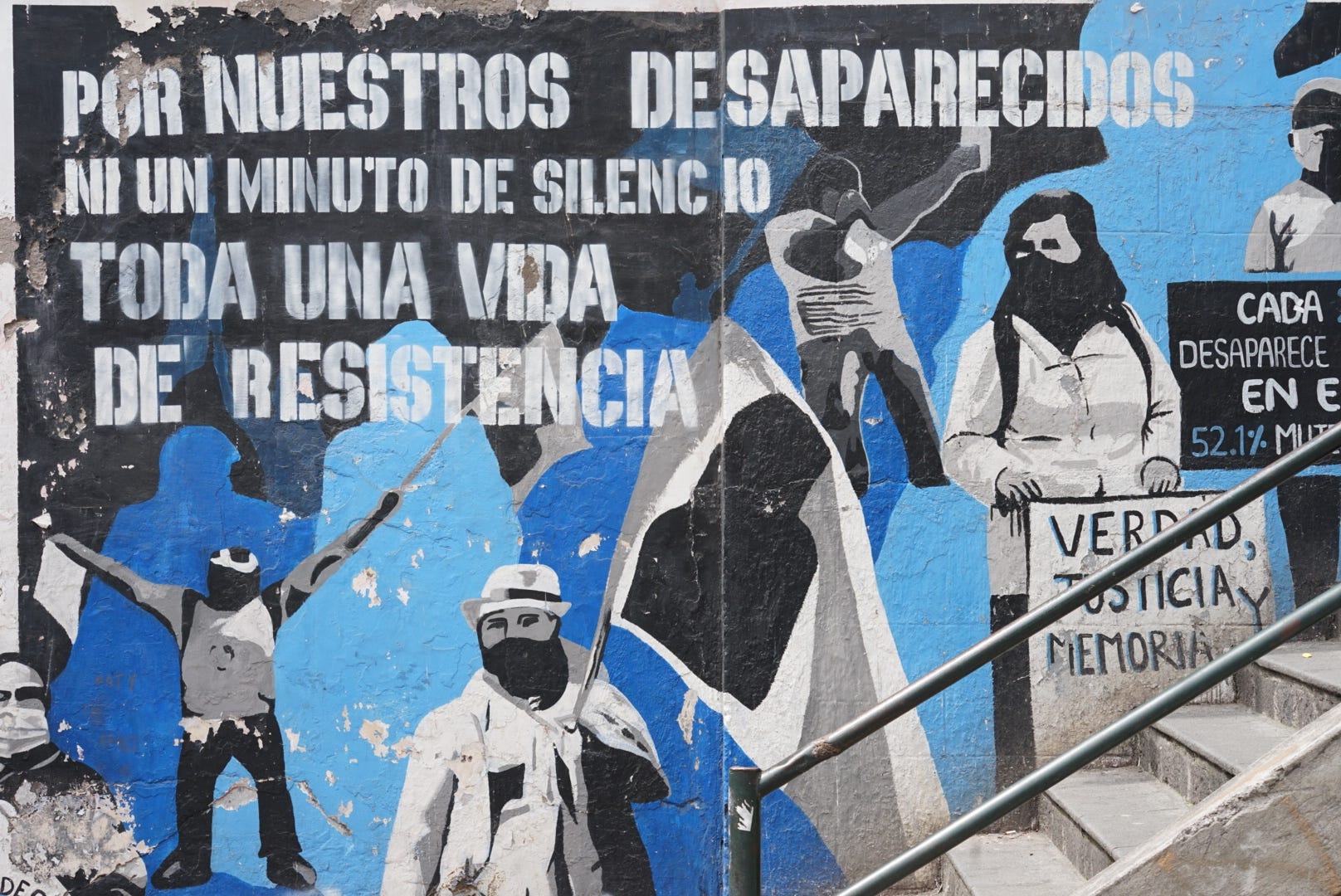

Voters, NGOs, and activists also worry about human rights abuses and constitutional overreach.

“We need transparency, we need the fraud to end, we need them to respect the voice of the people,” said Ricardo Almargo, who works in private security.

In December 2024, soldiers detained four Afro-Ecuadorian kids, the youngest of them 11. They were never seen alive again, but their charred bodies were found on December 24. The military denied any involvement but backtracked once security camera footage surfaced showing the arrest. Since then, they’ve admitted that the kids were picked up on suspicion of robbery but claimed they were later released alive.

There was no evidence linking the boys to a robbery and no record of them being released to the proper juvenile authorities. A judge has ruled that the kids were forcibly disappeared by the state and ordered an investigation, but the Ministry of Defense responded to her ruling with political threats.

The incident, known as the Malvinas Case, rocked Ecuador.

“The worst thing is that there are many more cases of children forcibly disappeared, their mothers are still looking for them,” Daisy Cornejo, a police officer, said while rocking a stroller with her infant son. “I am also a mother, and I would be devastated to not know where my child is.”

Experts confirm that the Malvinas Case is just the most visible in a slew of human rights violations, arbitrary detentions, prison torture, and forced disappearances since the internal state of conflict began a year ago.

“The problem is that society is so polarized that anyone who defends human rights is also [seen as] a criminal,” said a researcher who works in Ecuador’s prisons and asked to remain anonymous for fear of losing her job. “The point is… no one cares.”

“Something’s Gotta Give”

Noboa has capitalized on this polarization to expand his own power, first bending, then breaking what’s permissible under the constitution.

Judges have repeatedly ruled his internal conflict against the gangs unconstitutional as well as his repeated suspensions of vice-president Verónica Abad from office. In January, when Ecuador’s campaign season officially began, Noboa was obligated to transfer power to Abad. He refused to do so, violating both the constitution and campaign laws.

The CNE has been slow to respond and other state institutions have refused to weigh in at all. And though some voters are weary of this creeping authoritarianism, others willingly embrace it.

“Yes, he broke constitutional norms. But our constitution is trash, written by a leftist madman,” Luna said referring to Correa.

Given the slew of crises facing Ecuador, few of those who spoke to OffMap Media saw democracy as a top priority. Aside from security, economic growth seemed the most important issue to voters.

“Something’s gotta give. I’m voting to change this government” Marizela Carrion, who works in tourism, said. “We have nothing. Not education, not social benefits, not security. Nothing. Noboa has no idea what he’s doing.”

Since 2017, Ecuador has had the worst-performing economy in South America, according to a 2023 CEPR study, which found that poverty and inequality reached their highest levels in more than a decade even before the COVID pandemic pummeled the nation.

In 2024, unseasonable dry spells and a decade of infrastructural neglect collided, throwing the country into literal and metaphorical darkness with rolling blackouts that lasted up to 14 hours a day. Noboa’s administration was caught unprepared and has been slow to respond. Many small and medium-sized businesses shut down, further depressing an already reeling economy.

As of February 9, None of the candidates had presented concrete, financially viable plans to confront this — or any of Ecuador’s other looming challenges.

“I expected a candidate who could lead,” the vendor Sanchez said. “But none of them could explain their plan [for the country]. They just threw cheap shots at each other,” she concluded.

*A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that January was Ecuador’s most violent month on record. It is Ecuador’s most violent January on record (compared to other Januaries).

Excellent report, thank you guys for a great job!