Blood, Bribes, and Breakdown: The Fall of President Dina Boluarte

OffMap Media’s answer to the question ‘What the fuck happened in Peru this week?!’

Written by Anastasia Austin; edited by Douwe den Held

Late Thursday night, Peru’s Congress voted to impeach its president, Dina Boluarte.

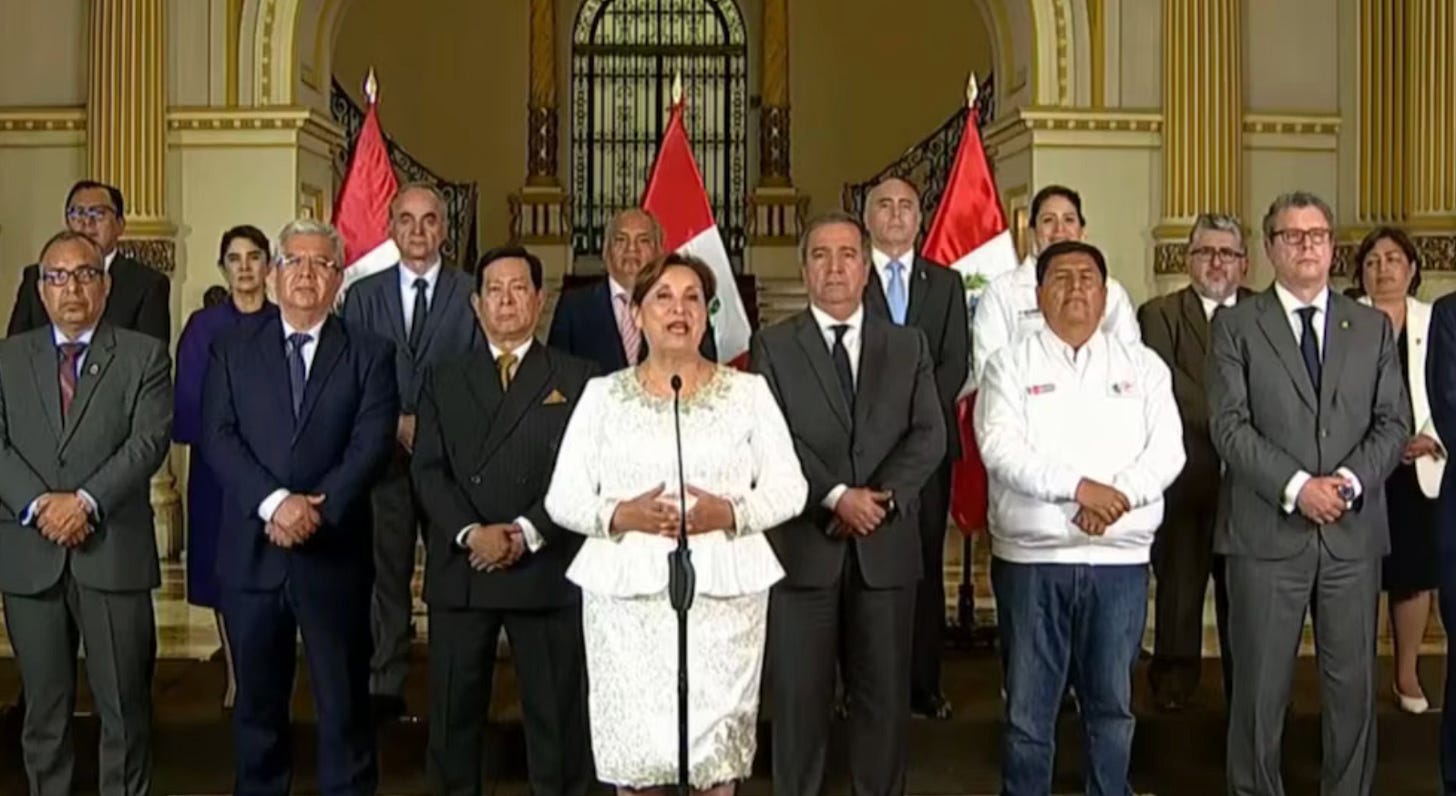

Friday morning, dressed head-to-toe in dazzling white and surrounded by her cabinet, she gave Peru the presidential version of the “you don’t know what you’re losing” breakup speech.

“At every turn, I called for unity, for working together, for fighting for our country. I have not thought of myself but of the more than 34 million Peruvians,” she said.

But, as Boluarte began listing her achievements, the broadcast cut to images of Peru’s former Congressional Chief, José Jerí. The 38-year-old Christian conservative was already being sworn into office as the country’s new president.

Boluarte’s exit – and the rapid manner in which it was executed – aren’t surprising for Peru. She held a near-zero approval rating in a country that has seen six (now seven) presidents since 2016, only two of whom were elected to office.

But the watershed that triggered her ousting is a litmus test for where the country stands politically. It comes as a direct result of an extortion-related massacre at a concert in Peru’s capital, Lima, last Wednesday, October 8.

That Boluarte’s former allies in the right-wing Congressional coalition chose now to turn on their rubber-stamp president highlights the importance of rising insecurity on the national political stage and says a lot about how the country’s political elite – especially on the right – are positioning themselves ahead of next year’s election.

A rough start

Presidential oustings have become par for the course of Peruvian politics in recent years. Since 2016, the Andean nation has had a revolving door of presidents as Congress made liberal use of the ‘permanent moral incapacity’ clause of the Peruvian Constitution.

“Incapacity is different from impeachment,” constitutional expert Javier Alban told OffMap Media.

“It means something happens, and we are left without a president. Historically, moral incapacity was used for a situation of mental illness. But when Fujimori escaped in 2000, Congress used permanent moral incapacity to sack him. It created a precedent. It was a terrible idea.”

Congress has weaponized the clause half a dozen times in the past decade in attempts to remove presidents.

In some ways, it’s surprising that Boluarte has held on this long.

Her presidency was beset by scandals, corruption investigations, and increasingly authoritarian policy initiatives. She started her tenure with an already low 19 percent approval rating, which by early 2025, had plummeted to just two percent – the lowest in the world.

Boluarte came to power in 2022, when her running mate and former president, Pedro Castillo, staged a failed and ill-advised coup. After announcing that he would dissolve Congress and rule by decree, Castillo attempted to seek asylum at the Mexican embassy. But Lima’s eternal traffic trapped the disgraced president, who is now in preventive detention, facing a 34-year prison sentence.

Vice-President Boluarte condemned her boss, and brokered a behind-the-scenes deal with the right-wing opposition coalition in Congress for their support.

For many in the Southern Andes, who voted Boluarte and Castillo into office in the first place, her actions amounted to a traitorous act against the left. Tens of thousands took to the streets demanding her resignation.

Boluarte responded by sending in the military and authorized security forces to use deadly force to quell the protests. They killed at least 49 people across the country. Thousands more were injured.

“The military was shooting point-blank. They fired from up close like madmen,” Yovana Mendoza, who heads a victims association and whose brother was killed by the army during the protests, told OffMap Media.

Boluarte refused to issue an apology.

Instead, the president and her right-wing allies perpetrated a narrative that the protestors were “terrorists” and pushed through policies that eroded institutional independence, waged war on the judiciary, and undermined civil society’s ability to hold power to account in Peru.

A long time coming

Having alienated her base, Boluarte became entirely dependent on her alliance with the right-wing Congressional coalition to stay in power. Paradoxically, her weakness is what allowed Boluarte to maintain her grip on the presidency for nearly three years, much longer than most others in recent years.

That right-wing coalition is led by Keiko Fujimori, whose father is the 1990s dictator Alberto Fujimori. Fujimori senior oversaw brutal militarization and unprecedented state violence against civilians amidst a war on the national terrorism group, the Sendero Luminoso. Peru’s Supreme Court convicted Alberto Fujimori of human rights violations and corruption in April 2009, sentencing him to 25 years in prison.

Keiko spent years trying to get a pardon for her father, finally succeeding in 2017. Alberto Fujimori spent his last years at home and died in September 2024.

Yet, his legacy has continued to drive his daughter’s – and hence Boluarte’s – political agenda. In one of her most controversial political moves, Boluarte signed a bill into law, granting amnesty to police, military, and self-defense committees for crimes committed during Peru’s internal conflict (1980-2000).

“It was like a bucket of cold water, to see the President in her Palace with those people who violated human rights, all smiling while signing that law. For us, it is a step backward,” Adelina Garcia, who has been searching for the body of her husband since he was abducted by the military in 1983, told OffMap Media.

With Boluarte signing every piece of legislation the Fujimoristas put in front of her, Congress has politicized institutions – including those responsible for checking government budgets and for appointing judges. It has weakened the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and pushed through laws that make it harder to counter crime and corruption.

“We are seeing institutions that were working until just recently, completely failing to support the people,” Mar Perez, a Lima-based human rights lawyer, told OffMap Media.

”The insecurity crisis owes much to the government itself, which has fueled it through laws that favor organized crime,” she added.

In response to government ineptness in the face of this crisis, as well as growing authoritarianism, tens of thousands of Peruvians took to the streets of Lima in mid-September. Since then, the self-proclaimed “Generation Z” protests have only gotten bigger.

Yet none of this – not the killing of protestors in 2022 and 2023, nor the accusations of accepting bribes and up to $500,000 in luxury jewelry, nor the myriad of other corruption investigations, and not even the dismantling of government institutions – were ultimately responsible for forcing Boluarte out of government.

Though lawmakers previously submitted eight impeachment motions over her tenure, the right-wing coalition led by Fujimori, who control roughly one-third of seats in congress, repeatedly blocked them.

That finally changed last Wednesday, when a cumbia concert went horribly wrong.

The Trigger

On October 8, unidentified armed men shot four members of the emblematic Peruvian cumbia ensemble, Agua Marina, during a performance at Círculo Militar, a well-known military social club. Two men on motorbikes managed to infiltrate security and open fire from behind the stage, injuring a vendor as well as the band members, according to authorities.

Band members told the media that they believed the attack was linked to the repeated extortion demands they’d received.

Though no one was killed, the incident caused waves of panic and indignation across the country. The reaction was particularly strong in Lima and other major cities in northern Peru, which have seen a sharp rise in extortion cases and criminal violence.

The ousting

As news of the attack and its alleged links to extortion demands spread, the Generation Z protests swelled and renewed their calls for Boluarte and members of Congress to step down.

Within hours, multiple lawmakers filed motions for Boluarte’s resignation, citing her government’s inability to stem surging violent crime and extortion.

This time, the right-wing coalition voted against the President. Congress gave Boluarte a chance to defend herself, but she declined, calling the procedure unconstitutional. This triggered a vote in which the president was impeached by a majority of 122 of 130 votes.

The fact that the right-wing coalition chose this moment to throw Boluarte under the bus, signals how they see organized crime and insecurity as the issues likely to dominate the April 2026 elections.

And, the new president, Jose Jerí, who is a part of this coalition, outlined their proposed militarized response in his first address to Congress.

“The enemy is out there on the streets: criminal gangs. We must declare war on crime,” he said. “Not only declare, but win it once and for all.”